Credit risk, the ever-present shadow in the financial world, looms large over institutions and investors alike. Understanding its nuances is crucial, and a key instrument in managing this risk is the credit default swap (CDS). This exploration delves into the intricacies of credit risk, examining its various forms and the role CDS play in mitigating its potentially devastating impact.

We will dissect the mechanics of CDS, exploring how they facilitate the transfer of credit risk between parties. This includes a comparison with alternative risk management strategies, a crucial element in understanding the comprehensive landscape of credit risk mitigation. The discussion will further analyze the interplay between CDS spreads and market perceptions of creditworthiness, highlighting the dynamic relationship between these key indicators.

Introduction to Credit Risk

Credit risk is a fundamental concern for any financial institution, representing the potential for financial loss stemming from a borrower’s failure to meet their debt obligations. This risk permeates various aspects of the financial system, from individual consumer loans to complex corporate debt structures. Understanding and mitigating credit risk is paramount for maintaining financial stability and profitability.Credit risk encompasses the possibility of losses arising from a borrower’s inability or unwillingness to repay a loan or other form of credit.

This broad definition includes several subtypes, such as default risk (the risk of complete non-payment), downgrade risk (the risk of a borrower’s credit rating falling), and migration risk (the risk of a borrower’s credit quality deteriorating). Sources of credit risk are equally diverse, ranging from macroeconomic factors like economic downturns and interest rate changes to microeconomic factors like a borrower’s specific financial health and management practices.

The complexity of credit risk often necessitates sophisticated risk assessment and management techniques.

Types and Sources of Credit Risk

Credit risk manifests in various forms, impacting different financial instruments and institutions differently. Default risk, the most straightforward type, involves the complete failure of a borrower to repay their debt. Downgrade risk reflects the possibility of a decline in a borrower’s creditworthiness, leading to increased borrowing costs or difficulty in accessing future credit. Concentration risk arises when a significant portion of a lender’s portfolio is exposed to a single borrower or industry, increasing vulnerability to a single point of failure.

Furthermore, the sources of credit risk are multifaceted. Economic downturns can trigger widespread defaults, while industry-specific shocks can disproportionately affect lenders exposed to that sector. Individual borrower characteristics, such as their financial history and management capabilities, also play a crucial role.

Real-World Examples of Significant Credit Risk Events

The 2008 global financial crisis serves as a stark illustration of the devastating consequences of widespread credit risk. The subprime mortgage crisis in the United States, characterized by the issuance of high-risk mortgages to borrowers with poor credit histories, triggered a cascade of defaults and ultimately led to the collapse of several major financial institutions. The crisis highlighted the systemic nature of credit risk, demonstrating how failures in one part of the financial system can rapidly spread to others.

Another significant example is the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008. The bankruptcy of this major investment bank sent shockwaves through global financial markets, underscoring the potential for even seemingly robust institutions to succumb to excessive credit risk exposure. These events underscore the critical need for robust credit risk management practices across the financial industry.

Credit Default Swaps (CDS) Explained

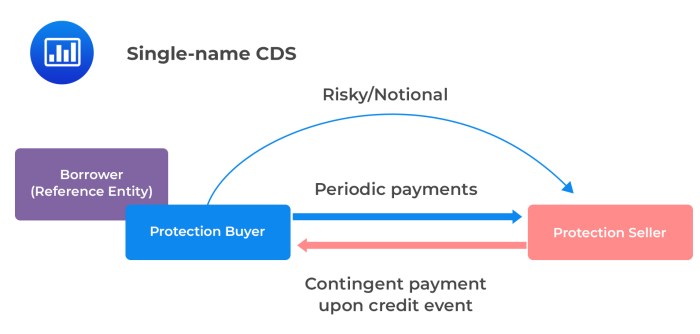

Credit Default Swaps (CDS) are a type of derivative that allows investors to transfer credit risk associated with a specific debt instrument, such as a corporate bond or loan. They function essentially as an insurance policy against the default of a borrower. Understanding their mechanics is crucial for comprehending how they are used in managing and mitigating risk within financial markets.A CDS involves two primary parties: the protection buyer and the protection seller.

The protection buyer is the entity seeking to hedge against the risk of default by a third party, the reference entity (the borrower whose debt is the subject of the swap). The protection seller, often a financial institution, agrees to compensate the protection buyer for losses incurred if the reference entity defaults on its debt obligations. The protection buyer pays a regular fee, known as the CDS spread, to the protection seller for this insurance.

This spread reflects the perceived credit risk of the reference entity; a higher risk equates to a higher spread.

CDS Mechanics and Functions

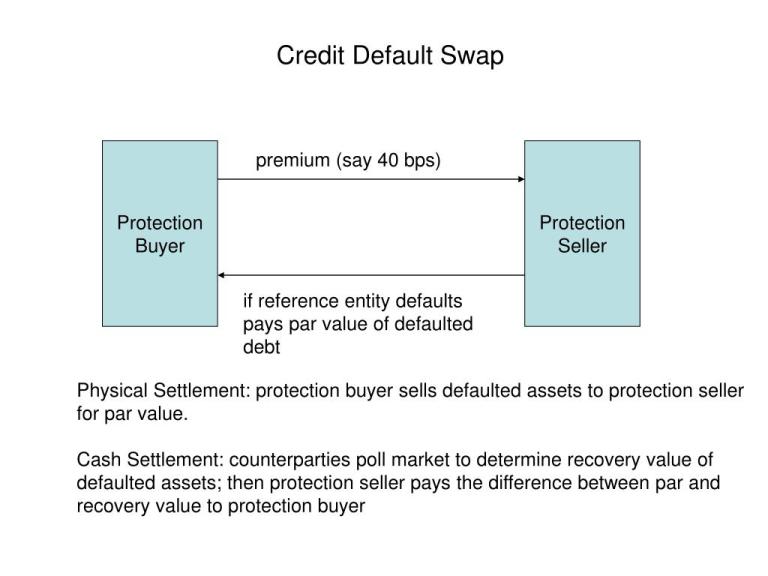

The CDS contract specifies the terms of the agreement, including the notional principal amount (the face value of the underlying debt), the reference entity, the maturity date of the swap, and the payment terms. If the reference entity defaults on its obligations before the maturity date, the protection seller is obligated to pay the protection buyer the difference between the face value of the debt and its recovery value.

The recovery value is the amount the protection buyer receives from recovering assets from the defaulted entity. This payment typically occurs after a predefined period, allowing time for the recovery process. Conversely, if the reference entity does not default, the protection buyer simply pays the agreed-upon CDS spread to the protection seller throughout the life of the contract.

The Role of CDS in Credit Risk Management

CDS contracts play a significant role in managing and transferring credit risk. They provide a mechanism for investors to separate the credit risk of an investment from its other attributes, such as yield or liquidity. For instance, a bond fund manager might purchase a CDS to offset the credit risk of a particular bond in their portfolio, allowing them to maintain exposure to the bond’s yield without bearing the full risk of a default.

Corporations can also utilize CDS to hedge against the credit risk of their counterparties or suppliers. By transferring this risk, companies can reduce their financial vulnerability and improve their overall risk profile.

Comparison of CDS with Other Credit Risk Mitigation Tools

Several other tools help mitigate credit risk. For example, credit rating agencies assess the creditworthiness of borrowers, providing investors with an independent assessment of risk. Diversification, the process of spreading investments across multiple assets, is another crucial risk management technique. Credit default swaps differ from these methods by directly transferring the risk, rather than merely assessing or diversifying it.

Unlike diversification, which reduces overall portfolio risk, a CDS focuses on managing the risk of a specific investment. Credit ratings provide information but do not transfer the risk itself, unlike a CDS which provides a direct financial mechanism for risk transfer. Therefore, CDS offer a distinct and targeted approach to credit risk management.

The Interplay Between Credit Risk and CDS

Credit Default Swaps (CDS) have fundamentally altered the credit risk landscape, creating both opportunities and challenges for market participants. Their impact stems from their ability to transfer credit risk, creating a secondary market for risk that can influence pricing and overall market stability. Understanding this interplay is crucial for navigating the complexities of modern finance.CDS impact the overall credit risk landscape by providing a mechanism for transferring credit risk from one party (the protection buyer) to another (the protection seller).

This transfer can reduce the concentration of risk within a single institution, leading to potentially greater overall financial stability. However, it also creates new avenues for systemic risk, particularly when a large number of CDS contracts are tied to the same underlying asset.

Benefits and Drawbacks of Using CDS for Risk Management

The use of CDS for risk management offers several potential benefits, but also presents significant drawbacks. Effective utilization requires a thorough understanding of both sides of the equation.Benefits include the ability to hedge against potential credit losses, improve capital efficiency, and gain access to broader investment opportunities. For example, a bank holding a large portfolio of corporate bonds might purchase CDS protection to mitigate the risk of default by the issuers.

This allows them to maintain exposure to the underlying asset while reducing their credit risk. Improved capital efficiency arises because the bank may not need to hold as much capital in reserve to cover potential losses. The access to broader investment opportunities stems from the ability to invest in riskier assets while simultaneously mitigating the potential downside through CDS.However, drawbacks include the potential for increased moral hazard.

Because CDS allow for the separation of risk from asset ownership, there’s a potential incentive for investors to take on more risk than they otherwise would. Furthermore, the complexity of the CDS market can lead to opacity and difficulties in accurately pricing and managing risk. The 2008 financial crisis highlighted the dangers of excessive CDS usage and the potential for systemic risk when large numbers of CDS contracts are linked to the same assets.

The interconnectedness of the CDS market can amplify the impact of defaults, potentially leading to cascading failures. Finally, counterparty risk associated with the protection seller must be carefully considered.

The Relationship Between CDS Spreads and Credit Risk Perception

CDS spreads, which represent the cost of purchasing CDS protection, are directly related to the market’s perception of credit risk. Wider spreads indicate a higher perceived risk of default, while narrower spreads suggest a lower perceived risk. This relationship is dynamic, constantly reflecting changes in market sentiment, economic conditions, and creditworthiness of the underlying issuer. For instance, during periods of economic uncertainty, CDS spreads on corporate debt typically widen, reflecting investors’ increased concern about potential defaults.

Conversely, during periods of economic expansion, spreads tend to narrow.

| Credit Rating | Typical CDS Spread (bps) | Implied Probability of Default | Market Liquidity |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAA | 10-30 | Low | High |

| AA | 30-60 | Low to Moderate | High |

| A | 60-150 | Moderate | Moderate |

| BBB | 150-300 | Moderate to High | Moderate to Low |

*Note: These are illustrative values and can vary significantly depending on various factors, including market conditions and the specific characteristics of the underlying asset.*

Credit Risk Assessment and Modeling

Accurately assessing and modeling credit risk is crucial for financial institutions and investors to make informed decisions and manage potential losses. This involves a multifaceted approach, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative techniques to understand the probability of a borrower defaulting on their obligations. Effective credit risk assessment goes beyond simply looking at numbers; it involves a thorough understanding of the borrower’s business, industry, and overall economic environment.Effective credit risk assessment employs a range of methods, blending quantitative analysis with qualitative judgment.

Quantitative methods rely heavily on statistical models and historical data to predict default probabilities, while qualitative methods incorporate subjective assessments of factors that may not be easily quantifiable. The combination of both approaches offers a more comprehensive and robust evaluation of credit risk.

Quantitative Credit Risk Assessment Methods

Quantitative methods leverage statistical techniques and historical data to assess creditworthiness. These methods provide a structured and objective approach to evaluating risk, allowing for comparisons across different borrowers and facilitating large-scale analysis. Common quantitative techniques include credit scoring models, which assign numerical scores based on various financial ratios and characteristics, and statistical models like logistic regression or survival analysis, which predict the probability of default based on historical data.

For example, a logistic regression model might use variables such as debt-to-equity ratio, profitability, and industry trends to predict the likelihood of a company defaulting on its loans. The output is often a probability of default (PD) score.

Qualitative Credit Risk Assessment Methods

While quantitative methods provide valuable numerical insights, qualitative assessments are equally important. These methods focus on subjective factors that are difficult to quantify but can significantly influence a borrower’s creditworthiness. Qualitative assessments involve in-depth analysis of the borrower’s management team, business strategy, competitive landscape, and overall industry conditions. For instance, a strong management team with a proven track record might offset some weaknesses in the borrower’s financial ratios, resulting in a more favorable credit assessment.

Similarly, an industry experiencing significant disruption might warrant a more cautious approach, even if the borrower’s financial statements appear healthy.

Hypothetical Credit Risk Model for the Renewable Energy Sector

A hypothetical credit risk model for the renewable energy sector could incorporate factors specific to this industry. Key components might include:

- Project-Specific Risk: This includes factors such as technology risk (e.g., performance of solar panels or wind turbines), regulatory risk (changes in government subsidies or permitting processes), and construction risk (delays or cost overruns).

- Market Risk: Fluctuations in energy prices, competition from other renewable energy sources, and overall demand for renewable energy would be considered.

- Financial Risk: Standard financial ratios (e.g., debt-to-equity ratio, interest coverage ratio) would be analyzed, but also adjusted to account for the specific characteristics of renewable energy projects (e.g., long-term contracts and revenue streams).

- Environmental Risk: Factors such as environmental impact assessments and potential liabilities related to environmental regulations would be included.

The model would use a weighted average approach, assigning weights to each factor based on their relative importance and historical impact on default rates within the renewable energy sector. This would then be used to generate a credit score or probability of default for a specific renewable energy project.

Step-by-Step Creditworthiness Evaluation

Evaluating a borrower’s creditworthiness involves a systematic approach.

- Data Collection: Gather financial statements, business plans, industry reports, and other relevant information about the borrower.

- Financial Ratio Analysis: Calculate key financial ratios to assess the borrower’s liquidity, profitability, and leverage.

- Qualitative Assessment: Conduct a thorough analysis of the borrower’s management team, business strategy, competitive position, and industry outlook.

- Credit Scoring: Use a credit scoring model, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative factors, to assign a credit score or probability of default.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Assess how changes in key assumptions (e.g., interest rates, commodity prices) could affect the borrower’s creditworthiness.

- Credit Rating Assignment: Based on the analysis, assign a credit rating reflecting the borrower’s credit risk.

This process allows for a comprehensive assessment of the borrower’s creditworthiness, providing a solid basis for lending decisions or investment strategies. The specific weights and methodologies used would vary depending on the lender’s risk appetite and the characteristics of the borrower and the industry.

Credit Score and its Relevance

Credit scores are numerical representations of an individual’s creditworthiness, summarizing their history of borrowing and repayment. Lenders use these scores to assess the risk associated with extending credit, influencing interest rates, loan approvals, and even insurance premiums. Understanding the components of a credit score and its impact is crucial for both borrowers and lenders.A credit score is typically calculated using a weighted average of several key factors.

These factors contribute differently to the overall score, with some carrying more weight than others. The specific weighting can vary depending on the scoring model used (e.g., FICO, VantageScore).

Credit Score Components and their Influence on Creditworthiness

The primary components of a credit score generally include payment history, amounts owed, length of credit history, credit mix, and new credit. Payment history is the most significant factor, reflecting how consistently an individual has made payments on time. Amounts owed refers to the proportion of available credit being utilized (credit utilization ratio). A high utilization ratio can negatively impact the score.

Length of credit history considers the age of the oldest and newest accounts, with longer histories generally indicating greater creditworthiness. Credit mix assesses the diversity of credit accounts (e.g., credit cards, loans, mortgages), while new credit considers the frequency of applications for new credit. Each component contributes to a holistic view of an individual’s credit risk profile. A higher score indicates lower risk, making it easier to obtain credit at favorable terms.

Examples of Credit Score Influence on Lending Decisions

A high credit score (e.g., 750 or above) can lead to lower interest rates on loans, mortgages, and credit cards. For instance, a borrower with a high score might qualify for a mortgage with an interest rate of 4%, while a borrower with a lower score might face a rate of 6% or higher. Similarly, credit card companies often offer lower APRs to individuals with excellent credit.

Conversely, a low credit score (e.g., below 600) can result in loan applications being denied or higher interest rates being applied. It can also make it difficult to rent an apartment or secure certain types of insurance. In some cases, even seemingly minor purchases like renting a car might be impacted by a poor credit score.

Best Practices for Maintaining a Healthy Credit Score

Maintaining a healthy credit score requires consistent effort and responsible financial behavior. The following strategies are crucial for improving and protecting your creditworthiness.

- Pay all bills on time, every time. This single action is the most important factor in your credit score.

- Keep your credit utilization ratio low (ideally below 30%).

- Maintain a diverse mix of credit accounts (credit cards, loans, etc.).

- Avoid applying for multiple new credit accounts in a short period.

- Monitor your credit reports regularly for errors and fraudulent activity. Dispute any inaccuracies promptly.

Case Studies

Real-world events offer crucial insights into the complexities of credit risk and the potential for catastrophic failures within the CDS market. Examining these cases helps us understand the interconnectedness of financial institutions and the systemic risks inherent in these instruments. The following case studies highlight the devastating consequences of insufficient risk management and the importance of robust regulatory frameworks.

The Collapse of Lehman Brothers

The bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in 2008 stands as a stark example of the devastating impact of interconnected credit risk and the failure of CDS to fully mitigate the risk. Lehman’s substantial exposure to subprime mortgages, coupled with a complex web of CDS contracts, triggered a cascading effect throughout the financial system. The firm’s failure led to a significant contraction in credit availability, amplified by the lack of transparency and the difficulties in valuing and unwinding CDS positions during the crisis.

The inability to efficiently manage and resolve the massive CDS exposure contributed to the severity of the financial crisis. Many financial institutions held large positions in Lehman-related CDS, and the failure to properly manage these positions led to substantial losses and further instability. This event underscored the systemic risk posed by interconnectedness and the importance of robust risk management practices, particularly regarding counterparty risk.

The 2012 European Sovereign Debt Crisis

The European sovereign debt crisis of 2012 presented another significant case study involving credit risk and CDS. The crisis centered on concerns regarding the solvency of several Eurozone countries, most notably Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Italy, and Spain. The escalating debt levels and the perceived inability of these countries to repay their obligations led to a sharp increase in the price of CDS on their sovereign debt.

This surge reflected a heightened perception of credit risk and the increased likelihood of default. The crisis exposed the limitations of CDS as a risk management tool in a sovereign debt context. The lack of a centralized clearing mechanism for sovereign CDS and the complexities of cross-border regulatory frameworks hindered effective risk management and resolution. The interconnected nature of European banks and their exposure to sovereign debt through CDS further amplified the crisis, demonstrating the importance of robust regulatory oversight and international cooperation in managing systemic risk.

| Case Study | Contributing Factors | Market Consequences | Lessons Learned |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lehman Brothers Collapse (2008) | Exposure to subprime mortgages, complex CDS web, lack of transparency in CDS valuation, insufficient risk management | Significant contraction in credit availability, amplified financial crisis, widespread losses | Importance of robust risk management, transparency in CDS markets, improved regulatory frameworks, and stress testing |

| European Sovereign Debt Crisis (2012) | Escalating sovereign debt levels, perceived inability to repay, lack of centralized clearing for sovereign CDS, cross-border regulatory complexities | Increased CDS prices, heightened perception of credit risk, amplified financial instability, international cooperation challenges | Need for stronger international cooperation, improved regulatory frameworks for sovereign debt, better management of cross-border risks, and stress testing of sovereign debt |

Future Trends in Credit Risk Management

The field of credit risk management is undergoing a rapid transformation, driven by technological advancements and evolving market dynamics. The increasing availability of data, coupled with the rise of sophisticated analytical tools, is reshaping how institutions assess and mitigate credit risk. This section explores key emerging trends and their implications for the future of credit risk management.The integration of big data and artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing credit risk assessment.

These technologies offer the potential for more accurate and efficient risk profiling, enabling financial institutions to make better-informed lending decisions.

Big Data and AI in Credit Risk Assessment

Big data analytics allows for the processing of massive datasets encompassing traditional credit information, alongside alternative data sources such as social media activity, online purchase behavior, and mobile phone usage patterns. This expanded data pool provides a more holistic view of a borrower’s creditworthiness, potentially identifying subtle indicators of risk that traditional methods might miss. AI algorithms, particularly machine learning models, can analyze this complex data to identify patterns and predict default probabilities with greater accuracy than traditional statistical models.

For instance, a machine learning model might identify a correlation between irregular social media activity and increased loan default risk, a relationship that would be difficult to detect using traditional credit scoring methods. This improved predictive power can lead to more precise risk pricing, better portfolio diversification, and ultimately, reduced losses. However, challenges remain, including the need for robust data governance and the potential for bias in algorithms trained on historical data that may reflect existing societal inequalities.

Challenges and Opportunities in the Evolving Credit Risk Landscape

The increasing complexity of financial markets, coupled with the rise of new technologies, presents both challenges and opportunities. One significant challenge is the potential for increased model risk as institutions rely more heavily on complex AI-driven models. Ensuring the transparency, explainability, and robustness of these models is crucial to mitigating this risk. Moreover, the rise of fintech lending platforms and decentralized finance (DeFi) introduces new sources of credit risk that require innovative risk management approaches.

On the other hand, the opportunities are substantial. Advanced analytics can improve fraud detection, optimize capital allocation, and enhance regulatory compliance. The ability to personalize credit offerings based on individual risk profiles can lead to greater financial inclusion and more efficient allocation of capital.

The Future Role of CDS in Managing Credit Risk

Credit default swaps (CDS) are likely to continue playing a significant role in credit risk management, albeit with some evolution. While CDS markets have faced scrutiny following the 2008 financial crisis, they still offer valuable tools for hedging credit risk and transferring exposures. The increasing sophistication of CDS contracts, coupled with the integration of big data and AI, may lead to more tailored and efficient hedging strategies.

For example, the development of bespoke CDS contracts based on granular risk profiles derived from alternative data sources could allow institutions to manage specific segments of their credit portfolios with greater precision. Furthermore, the use of CDS indices could provide more efficient ways to manage diversified credit risk exposures. However, the potential for market manipulation and the need for robust regulatory oversight remain key concerns.

The future of CDS will likely depend on the effectiveness of regulatory frameworks in mitigating these risks and fostering a transparent and efficient market.

Navigating the complex world of credit risk requires a nuanced understanding of both its inherent dangers and the tools available to manage it. Credit default swaps, while powerful instruments, are not without their own complexities and potential pitfalls. A thorough assessment of creditworthiness, informed by robust models and a keen awareness of market dynamics, remains paramount. The case studies examined underscore the importance of vigilance and adaptability in managing credit risk, a challenge that continues to evolve with the ever-changing financial landscape.

Query Resolution

What happens if the reference entity defaults on a CDS?

The protection buyer receives a payment from the protection seller, typically based on the notional principal amount of the CDS. The specifics are Artikeld in the CDS contract.

Are CDSs only used for corporate debt?

No, CDS can be written on various underlying assets, including sovereign debt, mortgage-backed securities, and other debt instruments.

How are CDS spreads determined?

CDS spreads are determined by market forces, reflecting the perceived credit risk of the reference entity. Higher perceived risk leads to wider spreads.

What are the regulatory implications of using CDS?

CDS are subject to significant regulatory oversight, aimed at mitigating systemic risk and promoting transparency in the market. Regulations vary by jurisdiction.